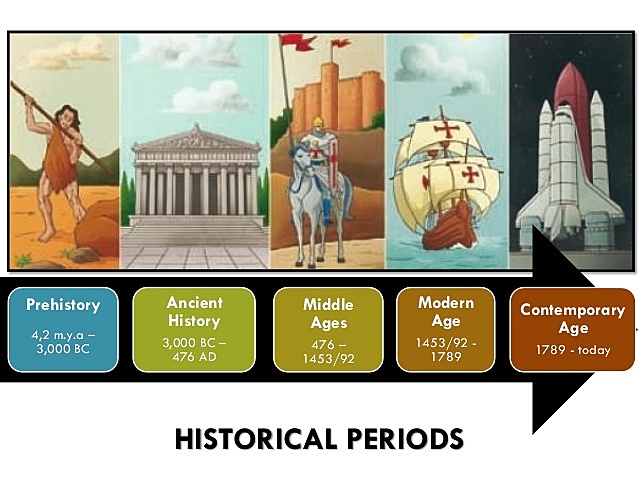

So now we finally reached the Middle Ages proper, High Middle Ages. A period in time between 1066 and 1350s. I did partially cover it in my article about 100 Years War, but there center focus was not the High Middle Ages themselves, but transition from it.

There are two often conflicting narratives as to what era was like. One like to talk about chivalrous knights, fair ladies and quests for Holy Grail and so forth. The other likes to portray it as dark and backward age, where backwards robber barons oppressed even more backward peasants as legacy of Rome lay dormant until Renaissance. The truth is both are far from reality. The former is nothing more than a fictional fairy tale and the latter is exaggeration.

Reality is that High Middle Ages had a lot more in common with High Roman Empire than initially apparent. Suddenly after all these tumultuous times we were back where we started. Autocratic rule together with bread and circuses. Just like during Julian dynasty Roman Empire there was stable stratified military government. The same unmoving social hierarchy. Even the same circuses to keep people distracted. Instead of gladiator fights there were jousting tournaments. Even slaughter of Christians was back on. Sure, population was thoroughly Christianized by now, but various Christian heresies started to spring. Thus, Catholic Church, in the interest of unity of faith of course (/irony), took it upon themselves to purge these heresies and burn all heretics in public squares just like Roman Emperors of the past did. Extensively decorated medieval Churches of Gothic style, such as Notre Dame de Paris were also made to keep people impressed and entertained.

Unlike High Roman Empire this era is closer to our current times, so issues are apparent. Supporters cannot whitewash it like they did with Roman times.

There were certain differences with Rome, however. Some might argue that more bureaucratic Roman style government did not return until Renaissance, but that would be misreading. Roman government that we know so much about only applied to the city of Rome itself and not to every province out there. We know little of how countryside used to run; most likely it was as autocratic as Medieval Feudalism. On the other hand, during Middle Ages cities did enjoy many statuary rights and a more democratic governance compared to feudal countryside. Once again, a lot of similarities.

Under Medieval Law cities had a governance outside of the usual feudal pyramid. Medieval lords understood importance of proper republican (democratic) governance in cities to ensure the craftsmen would do a proper work. Cities typically had elected counsels and mayors. In some cases, the whole city population could vote and in others only members of certain guild that was the major industry in that city.

While cities with Magdeburg rights did enjoy a certain level of privilege and democratic governance, the country lived different.

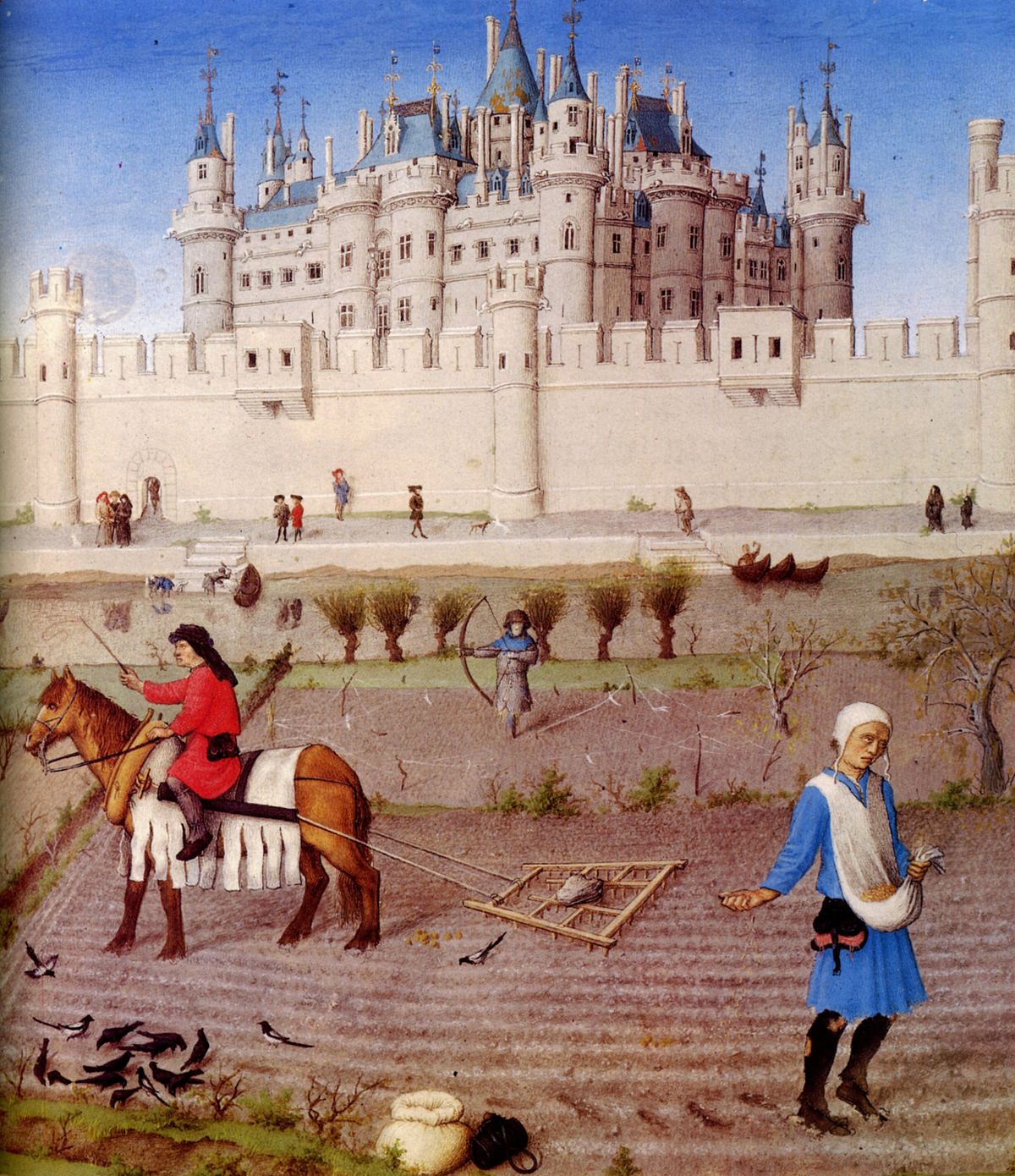

A centerpiece of country life was manor, which functioned a lot like Roman villa. Manor means not just the lord's mansion but all the fields and other structures that was needed for successful production of agricultural harvest.

Manor was run by a baron or his representative, vogt, who had to know enough about agriculture to effectively produce harvests every year. Baron or vogt would tell peasants when to plant, when to harvest as well as supervise their work to make sure it's done properly. Peasants were the actual manual laborers who worked the fields and did other rural manual labor.

Peasants were considered serfs legally, which meant they had certain obligations to the baron, whose territory they dwelled. Their labor was considered a payment for the protection from viking raiders and other thieves, the baron and his knights were providing. In that sense it was different from Romans who used slaves owned by villa owner as manual labor.

Peasants were divided into two distinct categories. First were villeins, who had to work on lord's fields and were provided with food and shelter. Second, more privileged one, were cotters who worked their own field but had to give their lord share of harvest from it. To be a cotter one had to be able to afford their own equipment and had their own agricultural skills.

Manors produced food and cities manufactured goods. That's how High Medieval economy worked. It was very well oiled and functioned stably and predictably. Population grew and many were likely content with how things were. That is until overpopulation became an issue.

Now we will come to the last part of the Medieval Society and top of the feudal pyramid, warrior nobility. Nowadays Kings are more of symbol of country than its military leaders. Sure, royals still get military education and serve in the military, but nowadays it's more of a tradition than necessity. Back in Middle Ages that was different. Kings and every peer had to fight very often; many spend a lot more days on military campaign than elsewhere. That applied to both Kings, every single baron and knights.

Barons were not just beneficiary owners of their estates, far from it. Just like peasants under them they were subjects to the King. Just like they collected fraction of harvest from cotters they themselves had to pay King his dues every year. To too this all up they also had to fight in King's wars if summoned to do so as well as maintain a certain number of battle-ready knights together with their horses and equipment. Disliked by peasants and dubbed robber barons, they themselves were helpless middlemen between peasants of their manor and count or earl that sit over them in the feudal pyramid.

Erls or counts in continental Europe were barons' direct superiors. Each Earl supervised several manors and barons there were his vassals. Area each Earl or count supervised was called county, hence the name. They were middlemen between barons, collected taxes from them and passed them on to their own superior duke.

Dukes were final middlemen between Earls and King himself. Many but not all of them, were of royal blood: sons, brothers and cousins of the King. Despite that their place in the hierarchy was one step below king. King was the ultimate superior of everyone in the Kingdom and owner of all land. Dukes were tenants under King and owed him taxes and service. Earls were subtenants under Dukes and so on down the pyramid.

Yet not even King would be the ultimate lord of it all: it would be God. Pope would be God's middleman between him and Kings of Earth. That feudal pyramid gave Pope a lot of authority. That is why Kings would have to ask Pope for divorce and other such things. That also explains why church figures like to praise Middle Ages as something good. They current power is but a shadow of what they used to have.

List of peers also includes Markies and viscount, but these two were special cases of basic count. Markies was a count of a county on a border with a foreign power. Markies was except from tax because he has to keep his county fortified. Welsh marcher lords were one such example. Markies often retained their privileges even when their county ceased being border one.

Viscount was created if a King would allow a count to split his county between his two heirs. In that case a splinter county would not be considered a full county, and its lord would only be called viscount, one step below count. The main heir would still be count though.